I hope you never become a member of this club, and an essay about recovery

A break before I post Part 2 of the Journey journal tale, which goes up later this week.

October 9th. Is it maudlin to observe this 'anniversary'? I have this internal push and pull every year about it, and we were talking with friends very recently about how over the last few years we'd forget the date had significance, until something like a story in the local news would remind us. It reinforces for me that humans can be very resilient.

So, yeah, I post these because I'm willing to share what happened that night in 2017 and because I think it helps people understand just how devastating a disaster can be, and maybe take away a better sense of how to help survivors (the first thing to know: the said with best intentions "But, in the end it's just stuff, just things, right?" is bullshit, so don't think that's helpful.

My friend Brian Fies critically acclaimed graphic memoir of the 2017 fires, A Fire Story, remains, for me, the most effective, poignant record of that time. The graphic novel medium, especially in Brian's talented, capable hands, facilitates an empathetic intimacy in a way that's hard to match with just the written word. It's powerful and personal.

Below are: a 2019 story from our local newspaper about that night (in which I am described as a "retired roadie," which tickles me since I 'retired' in 1988...), and an essay I wrote for Real Simple magazine about our recovery.

I hope none of you ever become a member of the club no one wants to be a member of. If you are a member, I hope you've reclaimed your life. If you know a disaster survivor, I hope you take some of what you read and use it to better understand how to assist their recovery.

MWH

(Please note: this story is from two years after the fire)

Santa Rosa man, Berkeley firefighters save corner of Coffey Park from Tubbs fire – Their staging area engulfed in flames, firefighters kept driving until they found some houses to save. AUSTIN MURPHY, THE PRESS DEMOCRAT, September 27, 2019

On a recent weekday morning Mike Harkins stood at the east end of Towhee Drive, admiring an arresting tree with dazzling, reddish pink blooms.

“That's a crepe myrtle,” Harkins said. “I know because we used to have one. Now, I see them everywhere.”

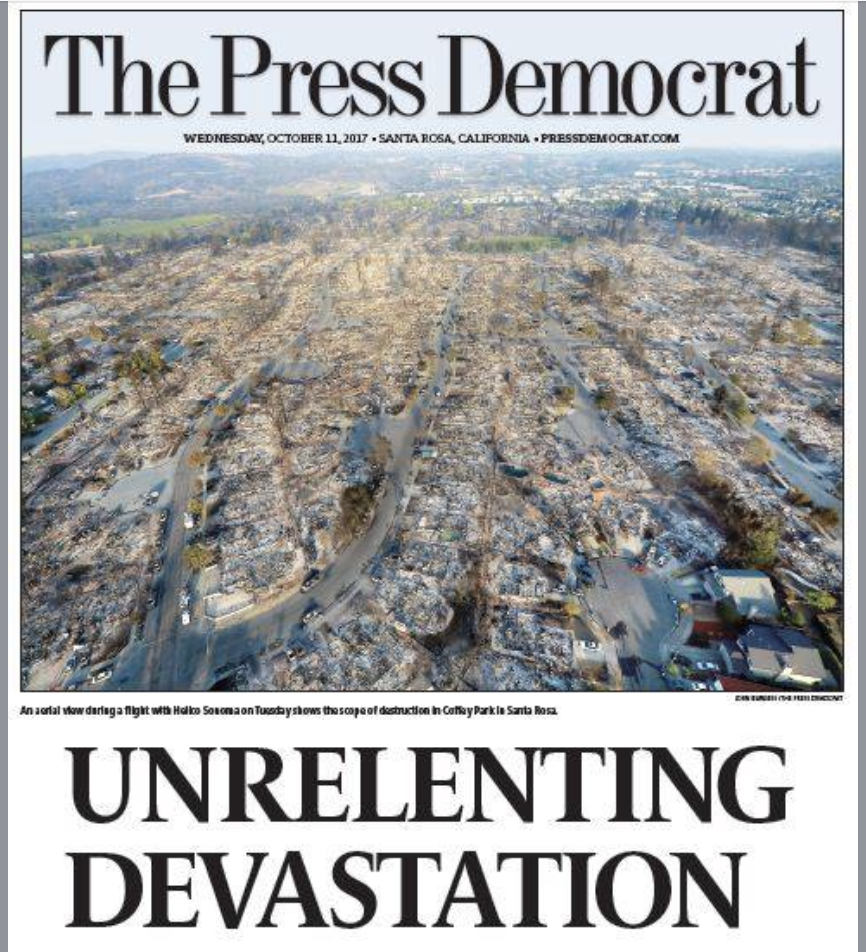

Named after a species of sparrow, Towhee can be found in Coffey Creek Estates, a 33-home subdivision in the southwest corner of Coffey Park. Eighteen of those homes were lost in the catastrophic October 2017 Tubbs fire, which destroyed 1,400 houses in Coffey Park alone.

This is the story explaining why there are crepe myrtles at one end of Towhee Drive, but not the other. It's also the story of how a team of firefighters from Berkeley and San Francisco saved the remaining 15 Coffey Creek homes, with a little help from Harkins, a retired rock 'n' roll roadie who spent the early hours of Oct. 9, 2017, in the gray area between courage and foolhardiness.

"A jet stream of embers"

A longtime roadie for the band Journey, Harkins is a night owl.

“The concert industry is a late-night thing,” he said. “So I was up.”

Channel surfing on TV early that morning nearly two years ago, he heard a news reporter say the blaze had jumped Highway 101. At that point, he and his wife, Elizabeth Palmer, “started to pack a few things.”

Taking a walk up to Towhee, Harkins looked east, to Coffey Lane. A steady stream of cars were evacuating. “And I thought, it's time to go,” he recalled. He repeated those words throughout the morning - “It's time to go” - but his heart was never in it.

Each would drive a separate car, they agreed, and meet at Elizabeth's law office on Stony Circle. After taking the left onto Towhee, she first saw that apocalyptic orange glow to the north, and had to work to fend off panic.

Elizabeth stopped on Sansone Court, at the home of her friend, Jennifer, whose husband Matt had gone to alert the elderly couple next door. By now it was after 3 a.m. Power was out, and the neighbors couldn't open their garage door. Matt got it open.

“We don't drive at night,” one of them told him.

“You do now,” he replied.

After telling Elizabeth he'd be close behind, Mike Harkins delayed his departure. He made the rounds in his neighborhood, knocking on doors, ensuring folks were up. He helped his elderly, wheelchair-bound neighbor Maria into her van and made sure she was safe.

And then, Harkins … stayed behind. Out on Towhee, he was stunned to see what he describes as “a jet stream of embers” flowing from the north. Embers were igniting bushes along the fence line of his Towhee neighbors, Bill and Nancy Adams. When he wasn't hosing down his house, and those on either side of him, Harkins was stomping out spot fires, including those in the bushes along the Adams' fence.

In the hours that followed, the fire advanced east on Towhee, and south along Sansone Court.

Harkins held his ground. If things got too dicey, he'd head for his pickup, parked at the east end of Towhee, where three posts prevented cars from accessing Coffey Lane. By pulling out the middle post, Harkins left himself an escape route. It also helped, he concluded later, that he had no grasp of the magnitude of the disaster, despite hearing pops and explosions that he later learned were the detonations of hot water heaters and car fuel tanks.

At some point before dawn he heard a “whoompf.” After spreading south down Sansone Court, the fire had crossed a grassy common area - “it had outflanked me, essentially” - and ignited the car cover over the Mustang in the driveway of his neighbor, Tony.

As Tony's house went up, Harkins fought the flames until the heat blistered his left forearm, pushing him back.

The south-facing wall on his own house begin to bubble, he recalled, before it suddenly ignited. Despite the futility, he kept hosing down the unburned parts of his house, dimly aware of the sound of chainsaws to his left.

Firefighters made their stand

Before they went to sleep that night, Mike Shuken recalled, firefighters at Berkeley's Station 4 said that the wind was picking up.

“So there was a little bit of talk about the potential of fire breaking out, and what we would do,” said Shuken, a 49-year-old firefighter and paramedic. “And then we went to bed.”

The call came at 4:30 a.m. There was a fire in Wine Country. They were instructed to respond immediately.

Shuken was on Engine 6, which met up in San Rafael with four engines from Station 15 of the San Francisco Fire Department. As that five-engine strike team sped north, Shuken shot video with the iPhone strapped this shoulder. It's typical to record unusual events, for training and other purposes, he said, provided it doesn't interfere with their work.

Shuken's 11-minute video of the inferno awaiting them went viral, and has since been viewed “6 or 7 million times,” he said.

The strike team had been instructed to stage in the parking lot of the Kmart on Cleveland Avenue. When they arrived, however, the Kmart was completely engulfed. The team moved north, then west on Hopper Avenue, past a gas station shooting flames 100 feet in the air, then south on Coffey Lane.

As they moved through the razed neighborhood, “we looked out at what appeared to be farmland,” Shuken said. “Oddly, there were little pinpricks of fire in the field. We couldn't quite figure out what we were looking at, and then it dawned on us that this was a subdivision that had burned to the ground, and the pinpricks were the gas supply lines.

“That was the moment we realized how catastrophic this fire was,” he recalled.

Driving south on Coffey Lane, recalled strike team commander Pablo Siguenza, a captain from San Francisco's Station 15, they witnessed block after block of “houses completely on fire, burning to the ground, nobody on it, no resources around.”

Finally, they got to the “edge of the fire,” he said. The team turned right onto Sansone Drive, not to be confused with Sansone Court, and found a hydrant.

To get at the flames, firefighters chainsawed their way through a backyard fence, then pulled their hoses onto Canary Place. Not quite two years later, Shuken remains incredulous at the sight that greeted them.

“We're looking at a wall of flame, 10, 15 houses completely involved, and here's this guy, standing there with a garden hose, squirting water on his house. And he turns around and says, ‘Thank God you're here!'”

Staying behind, disobeying evacuation orders, “is not something we advocate,” Shuken said. “But Mike Harkins is one of the braver guys I think I've ever met.”

Standing beside Harkins, Shuken trained his hose on his house. After half a minute, both realized it was no use. After turning off his hose, Shuken turned to the stranger.

“He looked me dead in the eye,” recalled Harkins, his voice cracking briefly. “And he said, ‘I'm sorry we couldn't save your house.'”

The Coffey Creek houses still standing would be saved. After Harkins pointed out a hydrant at Towhee and Canary, “we stuck our engine right in front of that hydrant,” Shuken recalled, “and that's kind of where we made our stand.”

The other vehicles backed in, and the team “ran five or six hose lines off that single engine,” Shuken said. “We were able to really stop the fire at the point.”

Bonds with first responders

Across the street from Harkins, Marilyn Allen and Chuck Frampton and his 10-year-old twin boys had piled into the car and evacuated about 2:30 a.m. After dropping the twins with their mom, Chuck and Marilyn returned to Canary Place at daybreak.

All the houses on the west side of Canary, including Harkins', were lost. But all those on its east side, including theirs, were saved.

Marilyn's joy at the sight of her standing home was muted by fear that she might still lose it. All around them, fires thought to be extinguished were flaring up.

Although they were not allowed to be there, “We refused to leave,” she said. Using hoses left behind by the strike team, they drenched hot spots. Chuck, a former Marine and retired sheriff's deputy, used his ladder to check the roofs of the neighborhood's surviving homes, cleaning gutters, extinguishing embers and trimming back branches.

With another couple who stayed in the house with them, they slept in shifts for the next few nights. Every hour, one of them would tour the surrounding streets, making sure nothing was on fire.

Two weeks after the fire, they were part of a deputation from Coffey Creek that made the drive to Berkeley to thank some of the first responders who'd saved their homes.

“We brought lots of cards,” said Marilyn, an emergency room nurse.

“And beer,” Chuck said. “Good beer.”

Married last month in a civil ceremony, Chuck and Marilyn recently received a wedding present from one of the Berkeley firefighters.

Next month, they intend to celebrate their marriage with a more formal ceremony. Serving as the “officiant” will be Harkins, who hasn't spoken to Shuken since the morning they met.

But the indelible sight of Harkins standing there, hose in hand, has stayed with Shuken, who said that “Mike's bravery and grit” represent, in his mind, “the people of Coffey Park and Santa Rosa. With people like that, you know this community's coming back.”

“Saving Grace” by Michael W. Harkins, Copyright 2019

All rights reserved, Real Simple magazine, September 2019

NINETEEN YEARS we’d driven, jogged, and walked through our Santa Rosa neighborhood, its people, houses, landscaping, and street signs as familiar as our reflections in a mirror. So as I looked at it on an October morning in 2017, my brain fought what I saw: This is not right, can’t be right. There is nothing to see here except scorched earth; where is everything? Stop screwing around and let’s go home...

The unimaginable surrounded us. Blackened trees and chimneys, some collapsed, others like tall, brick tombstones, rose out of an ugly landscape. Metal garage doors draped across incinerated cars. Contorted refrigerators and water heaters stood among wide plots of ash.

We gathered with stunned neighbors filtering back into the neighborhood. All of us had evacuated safely. I had seen the house die before my eyes. Elizabeth, my wife, experienced the more brutal loss, having driven away from our house and then returned to...nothing.

For the moment all we could do was stare and cry together.

I’d taken off my wedding ring the day before to do some work, left it on the kitchen counter. We’d never find it, though neighbors whose homes across the street had survived spent hours helping to look for it. Elizabeth lost her birthday necklace, saddle, and the cherished wall hanging of a horse in full stride. Gone were my earliest, typewritten manuscripts, illustration portfolio, our books, bills, jewelry, external hard drives, favorite shoes, antique bedroom furniture, birth certificates, and passports.

A mere eight hours before, the evening news had reported on a wildfire moving toward us, only a few miles away. Then the power went out. I checked outside—no fires around us yet, but a pervasive smell of smoke; warm, unrelenting wind; an eerie, glowing orange sky; and a slow, continuous procession of cars on our main thoroughfare.

Between the heavy evacuation traffic and growing uncertainty, we felt it was time to go. I assured Elizabeth I’d leave when I knew that neighbors Maria and Dane were on the road. We kissed goodbye and she backed out of the driveway. A minute later she texted, “Fire at the edge of the neighborhood!” Amid a jet stream of embers, she had pulled over and waited for our friends Jennifer and Matt as they loaded up clothes, dogs, and pet chickens, then followed her to her office a few miles away.

Dane and Maria got out OK. The neighborhood emptied, Elizabeth texted, wondering why I hadn’t left yet, and I responded: “Still safe.” I could see the fire’s spread a block or two away, but I felt if I could keep the increasing numbers of small fires around us from spreading, our street might be all right. I ran continuously, one end of the street to the other (stomp small fires), deck to fence (douse with paltry water pressure garden hose). Repeat. Quicker.

At some point I couldn’t stop running long enough to text anymore.

THE FIRE CAME IN THE MORNING, taking Tim’s, Tony’s, briefly skipping over ours to Maria’s. Embers burned through the back of my shirt as 40-foot flames rose on both sides of our house. The walls blistered, wispy smoke appeared, and moments later superheated air ignited everything.

I captured a picture before I left, a deathbed portrait of our home and all it represented, then texted the saddest string of words to the most important person in my life: “I’m sorry, I couldn’t save the house.”

It had been hours since Elizabeth had heard from me. My message reassured her and crushed her, and for a full minute she struggled to breathe, trembling uncontrollably, thoughts swinging wildly from relief that I wasn’t hurt, or dead, to the overwhelming reality that we’d lost our home.

I pulled into her office parking lot. She was waiting outside. We held each other, and held, and held. We were the displaced survivors you see on the news, two among thousands, whose worldly possessions consisted of whatever was in the car as we fled what was, at the time, the worst wildfire in California history.

NEWS REPORTED ON ANOTHER FIRE 10 miles west, near our friends Priscilla and Tom, and where Priscilla boards Elizabeth’s retired horse, Greycie. Elizabeth reached out, asked Priscilla if everyone was safe. The report was erroneous, but Priscilla hadn’t yet heard about Santa Rosa.

Elizabeth said, “Our house is gone.”

Priscilla responded, “Come here.”

We arrived to Priscilla’s open arms, emotionally wrecked but in an enviable position, with food, a bathroom, and a bed. We quickly had the basic comforts that thousands were without at this worst moment of their lives.

Later, in “our” room, we agreed that recovering from this would be a long-distance run, not a sprint. When (not if) one of us reached the can’t-take-this precipice, the other had to be the pillar of “we’ll get through this.”

We woke in the morning as if we had merely blinked and today was still yesterday. We thought about all the families striving for normalcy in packed emergency shelters, and of those like us, with friends but without the personal spaces that just yesterday contained everyone’s personal everything. We saw each other everywhere, us survivors, in cars packed with clothes, and in stores, where cashiers began to recognize “the look,” asking gently, “Did you lose your house in the fire?” When we said yes, they said, “I’m so sorry,” and meant it.

THREE DAYS AFTER THE FIRE, Priscilla called Mike and Denise, her neighbors who had a furnished guesthouse. She asked if they’d be willing to discuss renting to us, and Denise said, “We’ve been thinking we have to do that for someone. Come over.”

We got to know each other as best we could in this oddest of situations, at their table and looking out a window toward Santa Rosa, 10 miles beyond the rolling green hills, trees, and distant vineyards surrounding their house. We had things in common: spirituality, healthy lifestyles, music appreciation.

We had broken hearts. They had big hearts. There were small connections. They “knew” Greycie, Elizabeth’s horse, because they had seen her for years in her pasture across the driveway. Elizabeth had visited Greycie on weekends, always noting the house with the cute guesthouse beside it. We came to easy agreement on rent, and even managed a joke about moving in with our two shopping bags of clothes, chosen from the dozens Priscilla offered us.

Denise asked, “Just give us a day to do a few things, OK?”

We were blessed with shelter provided by people who had known us less than 24 hours. We realized much later, based on the new pots and pans (the box still in the garage) and other appliances, that Denise used the extra day to bring in things everyone has and uses every day, unless your house has burned down.

Our days were a brew of numbness, grief, and required tasks—buying clothes, contacting family, friends, and our insurance agent, going to the FEMA disaster assistance center. We went to our house when we could (we couldn’t not call it that) and sifted through the ashes, sad miners seeking the smallest nuggets of our past lives.

We returned each day to solitude and healing. But it began to feel...wrong. We were houseless but not homeless, safe, warm, and recovering under blue skies and atop beautiful hills. A therapist provided a gentle, correcting perspective: “Don’t diminish what happened to you.”

DISASTER DID NOT STOP THE WORLD from turning. My birthday came and went. Then Thanksgiving. Christmas. If not for family, old friends, new friends, the counsel of therapy, and the kindness of our city, we could not have left the fire behind. Fire-survivor funds were created virtually overnight. Gift cards came to us from close and distant relatives. Elizabeth’s family surprised us with a full shoebox of photos, collected to replace some of what we had lost.

We struggled to balance the comfort of our peaceful but isolating healing place with the need to stay socially connected. Mike and Denise could feel this, gently pulled us into their social circle, and that circle embraced us. Priscilla and Tom became family—come for dinner; let’s watch the game and just hang out.

“Come here,” they said.

We slowly reconnected, inviting friends to see us. Several neighbors found temporary housing only a few minutes away, and we met for dinners, talked about rebuilding, and over the next few months came to know each other better than we had in the previous two decades.

WE ARE ALL STILL HEALING. In 2018, as the one-year remembrance of our disaster passed, wildfires burned in Southern California and another wiped out the entire Northern California town of Paradise. Even now, images from any disaster still evoke our own scorched memories, at a depth only understood by those who are members of a club no one wants to belong to.

We now live with what someone called the new abnormal. The why and how always matter in a disaster’s aftermath, but they are the abstract in our own recovery. Our emotional and physical scars will always connect us to that night, but, more importantly, they now represent the story of how we healed, and each chapter begins with the same two, powerful words: Come here.