Music’s Band of Brothers — On the Road

I was on the road when John Lennon died...

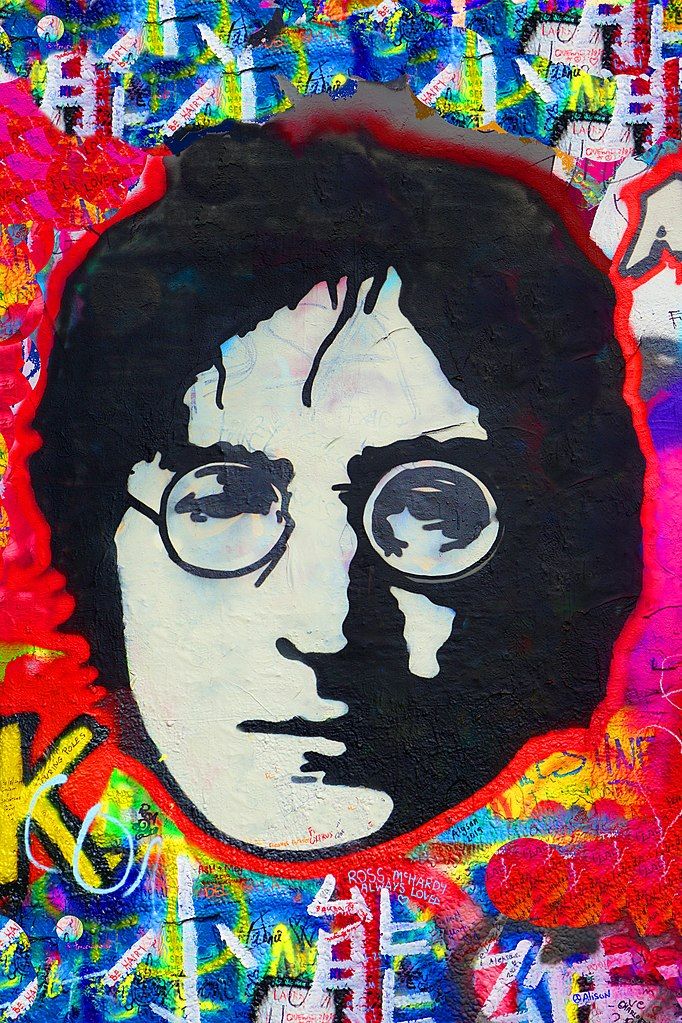

Hi everyone — time for my annual tribute to John Lennon, edited to keep it up to date. Do let me know if you experience any issues with links and other 'this damn Internet' kind of things.

Be safe, joyous, and grateful this holiday season. Thanks so much for reading (and tell your friends)!

MWH

I was on the road with The Babys when John Lennon died.

Since 2017, I’ve had to use the ‘net to find the dates of many music-related events that mean something special to me. First gig worked; first gig worked for pay; first music video. Stuff like that.

The wildfire that destroyed our house also turned almost all of my music and concert tour memorabilia to ash. It was chance that my tour jackets and a few other items were not in the house. Finding online information about tour dates and venues going back to the ’70s is a gawdsend. I have reclaimed specifics that inform my recollections, and I’ve also obtained some tangible items, like posters of shows I worked.

When I first wrote my Tribute to John Lennon — On the Road, I was unsure of what venue we worked that night. Now I know, via an online 2017 story in the Tribune Chronicle of Warren, Ohio, that we worked the Youngstown Agora.

It’s a tough date. Our collective psyche took a massive blow. Everyone felt its bewildering insanity and intense sadness. It’s impact is a secondary reason I wrote the essay. The primary reason was how deeply it impacted me as a gainfully employed roadie. Now, those of us who spent time in the Bay Area music community from the transformative mid-‘70s through the ‘80s are dealing with the aging of the roadies, production crews, and managers who birthed the modern concert event.

Death is the boss. The Covid years especially, and these last few years, especially, for us road dogs. We lost icons Herbie Herbert and John Villanueva two years ago, and this last year we lost Chris Tervit, a fellow Scotsman, who like his road partner Benny Collins (RIP), stage and production managed some of the '80s and '90s biggest tours. Herbie, Journey’s former manager (but I think better described as the band’s co-creator) died, eerily, 30 years to the day his mentor Bill Graham died in a helicopter crash. Herbie did for me what he did for many, many others, gave us the opportunity to be in rock and roll, to learn from him, to experience the music business, and life, in wonderfully unique ways.

His death shocked all of us here and throughout the music industry.

But then John Villanueva died unexpectedly, barely two weeks after Herbie, adding exponentially to our collective sadness. John, ‘Juan’ to many of us, was the first special spirit human I’d ever met. Here's my FB post just after I found out about his passing:

“John was Yoda, a beautiful, grounded, magical human. His beaming face can be seen throughout Santana's Soul Sacrifice in the film Woodstock, sitting on a road case behind drummer Michael Shrieve. Being on the road with John was like being on the road with some kind of rock and roll Dalai Lama. He was the universe in a carbon based life form.

I am so blessed that I shared the same space as John…”

Herbie and John, along with John’s brother Jackie, had a connection greater than DNA. Their history in music and live concerts was a compendium matched by few.

We’re gettin’ older, us road dogs, damn it.

The road goes on. Time’s arrow flies unswayed by our grief. Placeholders of my memories dot my life’s map, so that I may revisit them in fond sadness, melancholy, laughs, and gratitude.

With that happy intro, here’s my annual remembrance about where I was when John Lennon died, first posted in 2011 and lightly edited every year since then.

From a 2017 story in the Tribune Chronicle of Warren, Ohio:

The Babys — best known for such songs as “Isn’t It Time,” “Everytime I Think of You” and “Back on My Feet Again” — was headlining a show at the Youngstown Agora on Dec. 8, 1980, the same night Mark David Chapman murdered the Beatle outside the Dakota apartment building in New York City.

“We closed the show with ‘Head First’ and had gone off stage, hoping we’d get to come back on and do an encore,” Stocker said during a telephone interview. “We were at the side of the stage huddled with our road manager, who said the bus driver just came in. He was watching the news and said John Lennon had been shot.”

Gonzo and I were doing merchandise for The Babys, a band with good tunes that had been the opening act for Journey earlier that year (Journey would soon snag Jonathan Cain from The Babys to replace retiring Greg Rollie, keyboardist and vocalist).

I don’t remember specifics about exactly what I was doing when I heard the news. That’s one of the downsides of actually being part of the music and concert industry way back when, at least for some of us. I’ve always thought we were watching Monday Night Football, and we heard Howard Cosell make the announcement, but I just can’t be sure of that.

I do remember being stunned.

It just wasn’t what you’d expect. It was a foreign concept, that John Lennon would be shot and killed. It made no sense. Then again, with a few exceptions, it never makes sense whenever someone is shot.

But, John Lennon?

It hurt all of us, sure, but, me and Gonzo, we were in it, y’know? We weren’t rock stars, but we worked for a rock band. We didn’t hear our music on the radio, but we heard the music of the guys that we hung out with every night. We were getting good paychecks and having a great time because we were in the industry. Little tiny specks in the industry, certainly, but, in it, nonetheless.

We were in it, really, because of the Beatles. We were in it for the same reason young guys formed bands and played music and held on to a dream of someday doing nothing but playing music for a living, and living the music. We had those notions, for good or for bad, because we had been brought to the dream by the Beatles. I’m old enough to have gone to the Marquette Theatre, a south side Chicago kid, walking to the theatre on the corner of 63rd and Kedzie to see a Hard Days Night the day it was released (it’s where I also saw Ferry Cross the Mersey, with Jerry and the Pacemakers). I was already interested in the guitar before the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan, but me and thousands of other kids ramped up our dreams by learning how to play Day Tripper and every other Beatles tune we could figure out.

Hard to imagine that anyone else will come along in my lifetime and make a global, cultural change like the Beatles did.

And so there I was, in Ohio, having achieved some tiny level of satisfaction as a roadie, for bands that got airplay, that played concerts in small halls and big stadiums, and I was just doing it, living it, feeling it…

And John Lennon was dead.

Allow me to digress briefly: Years after Lennon’s death, the industry lost another great, when influential soul Bill Graham was killed in a helicopter accident. He didn’t have the stature of Lennon, but he was a major force in live music. Shit, he was THE force. The original Big Man, Clarence Clemons, had a condo just beyond my backyard in Sausalito, and we’d see each other, shoot the shit every now and then (I was on the video crew for some of the Born in the USA tour), and we saw each other the day after Bill’s accident.

Clarence looked at me and asked, “Now what?”

He was asking what so many of us Bay Area music-types wondered — how on earth do we fill that void? Who would we turn to now, who would keep things happening, who would put on shows that people would remember their entire lives, who could musicians and artists and managers and fans rely on to make the impossible possible, how would we ever find our way to nirvana without the guru?

That night in Ohio was a “Now what?” moment.

Everything would be the same after that, because everything keeps going no matter who lives and who dies, just as everything would be the same after Graham, but, just like it is for all our tragedies, personal and distant, nothing would ever be the same.

As I get older, I realize how powerful the “Now what?” moments are in our lives, and I grudgingly accept, with sadness, that the “Now what?” moments must occur, and all I can do is carry them with me, remember them, and use them to guide me, to remind me of how I should treat people, and make the most of every moment, because the next moment isn’t promised to anyone. Not to me. Not to you. Not to John Lennon.

Lennon and millions of other souls are gone, and I can keep asking “”Now what?”, but, more importantly, I think John Lennon would say it’s okay to ask as long as I move my ass down the road to look for the answers. It’s the moving that’s the answer; the journey is the answer; the knowing that life is full of “Now what?” and you may never know why, but the only way you’ll ever have a chance in hell of figuring out anything is to keep moving…

On the road.