If Steve, Then Steph

Steve Jobs had one producer during the NeXT and Apple years - Steph Adams.

Note before the note below: A 2023 update – since the original post, the complete If Steve, Then Steph story has been made available on Amazon, where for a brief period it became a #1 New Release. You can find it here.

Author's note: It's been ten years since the world lost Steve Jobs. In tribute to that remarkable man, here is the first of a two-part exclusive profile of another remarkable man, Steph Adams, Jobs' personal producer for over thirty years, who orchestrated the wonderous, Jobs' introductions of Apple's world changing products, from iTunes to the iPad.

Part One focuses on the early years and Adams' first interaction with Jobs, an interaction that changed the course of Adams' life. Part Two, available this coming weekend only to members, will reveal Adams' most memorable event (it won't be what you might think) and his toughest, saddest event – producing the Steve Jobs memorials.

Enjoy this deep dive into what was an extraordinary partnership.

MWH

Part One – The man behind Steve Jobs' curtain and how he got there

Those last few moments in the wings, stage right, were always whispers, as Steph Adams — headset buried in hair perpetually in need of a trim — neared the end of his pre-show, NASA-worthy checklist.

“Audio one.”

“Go.”

“Lights.”

“Go.”

Music cues, video cues, slide cues, house cues, stage cues, ‘talent’ cues, a constant check and check again while the last of thousands of attendees take seats.

Even the audience walk-in music was an element of producer Steph Adams’ checklist. “In the beginning I would pick some tunes to play before the show, but as the shows became world events and music became its own Apple product, we had this idea to develop the concept of ‘surprise and delight’ from the moment attendees entered through to the last ‘thank you.’”

So he and Jobs began to orchestrate the music to match each different show, often choosing songs from “whatever we had in our respective CD collections. Coming from the concert industry, I always went back to using music to build up the audience energy and anticipation. Most corporate gigs and clients just wanted music to fill any silence, like elevator music. Or they did it because that’s what everyone did.”

Sometimes as the show clock wound down, Jobs would be “chatting with his peeps, and I would float into the group, gently, and provide a time check. The group would break up and Steve would walk with me to our position in the wings.”

Jobs would lean against Steph, shoulder to shoulder, head bowed to Steph’s ear. “No personal bubble separated us, we co-habited the same space. I had his trust and he had mine.”

The only guy in the world who momentarily held back one of modern history’s greatest creators whispered, “On my count…Go,” the last cue, Jobs’ cue. Then, only loud enough for Jobs to hear, Steph would add “Break a leg,” live theatre’s traditional version of wishing a performer good luck. “And Steve, with everything that came with being Steve Jobs at that moment, never failed to say ‘Thanks,’ never failed to complete that moment between us,” before stepping on the stage to reveal tools with the same impacts as Gutenberg’s press, Bell’s telephone, and Marconi’s radio.

For decades, no one had anything like Apple's magic devices or the stage upon which Steve Jobs enthralled us, with shows of sophisticated production values rarely, if ever, seen in a trade show keynote. The Steve Jobs-Steph Adams collaborations, beginning in 1988, created showcases of beautifully restrained design, wickedly efficient message delivery, Grammy-level entertainment, and Hollywood level production.

Jobs understood what many didn’t: style mattered, to the academic and the artist, the doctor and the director. Merging great style with gracefully efficient ways to ‘do’ things would help create an amazing future.

For Jobs, flat out, why on earth wouldn’t you complement amazing technology with thoughtful, evocative design?

For Steph, flat out, why on earth wouldn’t you complement an amazing messenger and his message with focused, consistently classy production?

What Jobs found with Steph was another visionary who shared the same sensibilities, and an inherent expertise fed by heart, soul, and brain. He found a guy he could be a guy with, a relationship of trust, reliability, and commonality.

“I walked into a meeting once, Steve wasn’t there yet and we started discussing some show issues, and as I’m talking and looking at this plot print rolled out on the table, this voice in my ear says, ‘How were the holidays?’ and it’s Steve, and we go back and forth, and I said something about my kids presents, and he just smiled and said, ‘Well, it is all about the kids, isn’t it.’ Those moments mean as much to me as shooting the shit in his house about projection and colors, and shows. We were a couple of guys, a couple of fathers, just talking.”

These ‘guys’ created some of modern history’s greatest moments on stage, not just because of some stunning live entertainment experience, but because of a phone; a computer; a digital music player; an online music store.

All presented in what Adams calls “corporate theatre,” watched, envied, and eventually copied by Microsoft, Google, Oracle, Facebook, and other dominant Silicon Valley players; attended and followed by legions of fans, users, and journalists; eventually viewed on broadcast and cable news shows; and featured in the press.

But stunning live entertainment experiences did also occur. Guests and performers integrated into those shows included: U2, John Legend, Madonna, John Mayer, Kanye West, Mick Jagger, Alicia Keyes, Sarah McLachlan, Coldplay; film stars, TV stars, and international personalities; in venues from San Francisco to London, Paris to Japan.

And every show was assembled, orchestrated, and piloted by Steph and his company, Adams & Associates (A&A), since a fateful day over thirty years ago at San Francisco’s Davies Symphony Hall, and even though he has never been a NeXT or Apple employee.

He is incredibly easy going, loyal, and jovial, a talkative family guy who loves knowing and learning, likes cars and skiing, has an intense respect for bees, an unrivaled encyclopedic knowledge of the live events industry from technology to venues, and a Zen-like work focus known to family, staff, and production crews as “Steph mode.”

He also has a great sense of diplomacy and a respect for people.

“I’ve been told that I have the ability to talk to the executive team in the boardroom and make them feel comfortable about what’s going on, then go down to the loading dock and talk to the Teamsters about what’s happening and have them feel comfortable too. That’s important in my business.”

He readily acknowledges that those personal and professional attributes contributed greatly to his career, but, “I couldn’t have done any of this, none of it, without my family’s support, without my wife Linda.”

His eyes emphasize what he’s saying in a way more words couldn’t match.

They met during A&A’s early years. Steph booked his flights and hotels through Linda’s travel agency in Petaluma, a biggish-small town in Sonoma County, California. Linda remembers that, “he called to ask about what he needs to fly to Singapore, comes in to get his tickets, and we talked a bit. Before he left, he asked if I’d ever been to Singapore, I said no, and as he left he said, ‘I’ll show you my pictures when I come back.”

He called, they met for lunch, and married five years later.

Twenty-six years on she can now more easily talk about the kind of accommodating life the family adopted during the NeXT and Apple years, the birthdays missed and other should’a-been-there-Steph events, and of carefully nuanced conversations with everyone from extended family to friends.

“I wouldn’t tell you where I’d been Friday night, I wouldn’t say what city Steph was in, I wouldn’t tell you Steph was out of town…” She also accommodated a necessary flexibility, like changing a spaghetti dinner for the family to a dinner for family and four guests at Steph’s office who were staying overnight before heading back to San Jose.

Or driving to Tahoe for a family Christmas holiday, and barely two miles into the trip Steph takes a call “about a meeting the next day that I need to attend, about a MacWorld show the first week of January.

“Linda made the travel arrangements while we drove, we got to Tahoe, got everyone settled in and then she took me to the airport for a flight back.

At a Christmas party, the man himself revealed he knew of and appreciated her, smiling and saying “Ah, you do exist,” as Steph introduced the two to each other.

Describing everything Steve Jobs was evokes a litany of vibrant, evocative platitudes — innovator, inventor, icon, and so on. His legacy is a rarity, his place in history and in memory the same: a man inseparable from his world-changing inventions and, as attested to by the Apple memorial’s 10,000 attendees and thousands of Apple Store employees viewing the tribute’s live-stream, a man loved and awed not only by the users of his technologies but by those who worked for his company.

That iconic status is why even a mere archival glimpse of Steve Jobs still intrigues so many of us. He was a carbon-based life form, but gifted with a vision and singular ability to manifest the future in the present. He was and remains a unique celebrity. We know his image, we’ve seen 12- or 20-second video clips of him, holding an iPhone, or standing in front of a huge, stunning screen image of a MacBook Pro. We can see, hear, and read about him almost at will, and we are all the better for it, better for having a kind of live-on-tape record we marvel at, dissect, enjoy, discuss, and strive to emulate.

Those clips provide slices of visual history, profound technological leaps presented to us with entertaining fanfare, much like movie premiers or new television shows, hosted by the only showman of his kind. ‘Hey, I’ve created things so great I’m not taking any chances that you might miss it, because I know this stuff is going to change the world. You need these things, and I believe it so strongly I’m going to put them in a show for you.’

At first thought, it seems nothing is unknown about Jobs. Books, films, newspapers, and magazines, everything has been revealed about the man and his creations. The record of his life, his work, his products, his philosophies, his family, it’s all out there. Draw a line, put little marks on it for each magical product introduction, and the space from one event to the next is easily filled with accessible information about Steve Jobs and Apple: what was happening in his personal life; the products’ development cycle; the designs, the design changes; the final products. The spaces between each magical introduction are chock full.

And yet the things with which we are all most familiar are the things we know nothing about — the shows and the people who created them.

Some of us were in the audience, more of us watched streams on our devices, and the rest of us — across the modern world — saw the important bits on the news, on TV, in print and digital publications. It’s all there for any of us, from Jobs’ demonstration of the first iPod’s circular navigation wheel, to his first finger scroll on an iPhone screen, to his last event, revealing iCloud during the World Wide Developers Conference (WWDC) at San Francisco’s Moscone Center in June of 2011.

As important to Jobs as anything else Apple, his keynotes, eventually recast as Stevenotes in the popular lexicon, so unique were his appearances, presented products and positioned them for success in a way no print campaign alone, no TV commercials, no banner advertisements could match. They were exactly what Jobs wanted, enhanced by people he trusted to make the reveals as good as he’d envisioned.

Adams became to Jobs’ events what Jobs was to the creation of our digital lifestyle — indispensable. For every Stevenote, Jobs, his teams, and Steph created a live story presentation emceed by a storyteller unlike any other.

Steph remained behind the curtain, unseen, for decades, rewarded not with publicly known accolades, but with the trust, friendship, and the thanks of the man he guided from the wings, Steph’s wings, for almost thirty years. There were, of course, moments between the two of them that were anything but rainbows and blue skies, because under the pressure of a show, sometimes the information came with an edge. “But I didn’t take it personally if he snapped at me, and he didn’t take it personally when I snapped back.”

During one technical rehearsal, a massive bank of iMacs, each running a single application that could display multiple videos and images, had some technical issues. Jobs, standing amidst the empty audience chairs, yelled to Steph on stage, “That’s not much of a video wall,” alluding to the different, unrelated images on the machines.

Steph responded, “That’s not what we had in mind for this.”

Jobs shot back, “That’s what I had in mind.”

Steph looked at him and said, “Whoever told you it would be a video wall doesn’t know what a video wall is.

That ended the brief discussion.

The tech rehearsal went on. For the show, the wall of iMacs operated as it was supposed to and looked great.

From the ‘90s with NeXT to shortly after Jobs’ passing, his in-house Apple aide de camp Wayne Goodrich was integral in the development of Jobs’ keynote content and worked closely with Steph. But it was Steph’s unique task to create and present the onstage Steve Jobs universe (still remembered by many as the ‘Steve Jobs reality distortion field’).

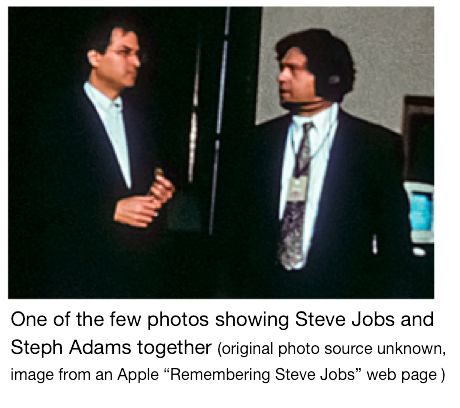

Their close relationship was once succinctly defined by Eric Lier, former Apple Senior Director of Corporate Events, who noted at one rehearsal that if there was a Jobs sighting in the house, Steph was somewhere close. Lier coined the phrase, “if Steve, then Steph.”

They did 40 or more shows a year, year after year after year, in the U.S. and internationally, many of those requiring weeks to build.

The Jobs era would come to an end in 2011, with the most emotionally cruel twist, something Steph never envisioned. He would have to take everything he’d experienced, everything he knew, and create the saddest, toughest show of his life, starring his friend who wouldn’t be there, who would never again lean against Steph to hear that whispered “Go.”

In a photo Steph keeps in his office, he stands proudly next to his 1971 class project, a black cardboard box mock-up of a computer, complete with flashing Christmas lights, data tape reels, and hand-drawn monitor screen.

It is the statement of a fifth grader who knows exactly what he wants to do for the rest of his life.

“There was a show on ABC television for years, The Wide World of Sports, kind of famous for the show’s intro clips of different good and not so good sports moments. Everyone wanted to be the athletes, but I wanted to be the guy who strapped a camera to my head, jumped in a sled and went down the hill. I thought that was very cool.

“I’d still like to do that.”

He got his creative eye from his mom. From his dad, an Air Force pilot’s and engineer’s inherent grasp of technology. He nurtured his childhood interest in computers and video (before those technologies were even familiar to most of us) into his young adult years. In the early ‘80s, even as he still attended classes on television broadcasting and production at San Francisco State University, he had already worked on several video shoots, including one with celeb chefs Julia Child and Paul Prudhomme.

He landed a job with the San Francisco office of Netcom, a burgeoning satellite company with additional offices in L.A. and New York City, and with an ahead-of-the-curve business model: acquiring and reselling transponder ‘time’ on satellites, creating a way for anyone to uplink and downlink a live, interactive video event to multiple locations anywhere in the country or, for those who could afford it, the world.

From 1983 to 1986 Steph produced many of the country’s earliest live, ad hoc satellite events, including a national anniversary celebration for the Statue of Liberty that required over 50 download sites, a massive undertaking at the time. Netcom also provided video projection systems for events and meetings. There is a plethora of projectors available now, but video projection for large spaces then was still embryonic, expensive, and highly technical for large venues, with somewhat more affordable solutions for meetings and small events (although still several thousands of dollars for a ‘more affordable’ video projector).

As Netcom’s San Francisco office built its client list, Steph often served as projector operator or on site producer for many Bay Area corporate and music events. It was perfect, “the job I’d have for life.”

Or so it seemed. Netcom crashed after only a few hot years, and when it filed for bankruptcy in 1986 the company owed Steph unpaid wages, a tough life lesson for a young man.

But he’d learned more than specs and tech during this time. He’d learned the business, and he envisioned a way forward. He accepted equipment in lieu of wages and began to build what would become Adams & Associates. “I got an aging van, one decent video projector, two projectors best described as suffering from deferred maintenance, two 10-foot screens, and a pile of assorted cables in plastic milk crates.”

He went to work, calling on his connections in the Bay Area. He also did a little quick, creative financing, and “I got a GE.”

In the projection industry, “GE” meant the $120,000 General Electric Talaria 5055 light valve video projector, a 125-lb, table-sized block of electronics, metal, and lenses that projected a video image onto a 20-foot screen 140-feet away.

It was the Ferrari of projectors, and maintaining it was just as challenging.

Work came his way, he established himself as dependable and, more importantly, knowledgable. Those attributes and his work attracted the notice of Pat ‘Bubba’ Morrow, road manager for Bay Area band Journey and VP of Nocturne, a new venture by the band’s production company, spearheaded by another Steph fan, Herbie Herbert, Journey’s manager.

The band, originally formed in the early ‘70s, led the ‘80s music charts and toured incessantly. It was also pioneering something new — using its own camera crews and directors to shoot live feeds during a show and project the video onto large screens for audiences at coliseums and large stadiums. The concept became a screaming success (fairly ubiquitous now at most live, large venue concerts), and Nocturne began providing concert video crews for other touring artists. Adams & Associates became one of Nocturne’s trusted vendors. Steph and his GEs went on tours with Journey, the Rolling Stones, U2, and Michael Jackson.

The critical element of the GE Talaria projector was its 12-inch diameter, rotating light valve, consisting of an oily fluid suspended on a thin slice of glass, which through the magic of physics, Schlierin optics (yep), a powerful lamp source, and an operator to continually monitor and tweak it, created the projected images.

To describe the machine as fickle does not do justice to the word fickle.

When everything was right, images looked great; when things weren’t right, because of an ambient temperature change or someone said something that upset the projector, images looked terrible. The projector’s popularity with organizations that could afford them was growing, as was an ongoing quest to find the few people who knew how to get the best out of the finicky machines.

“Getting that GE was one of my life’s ‘if not for that’ moments,” Steph says, because a company in San Francisco bought a GE to use for an important upcoming show and nothing about the machine was right.

October 1988: One glass-mounted slide determined Steph Adams’ future

The voicemail message was fairly direct, and from someone he didn’t know: “GE said to call you, we have a 7155 and, well, no one knows how to operate it.”

Steph was one of two techs on the West Coast that GE technologist Bill Baldwin said could fix any problem with a 7155. But, “the first thing I did was call him and ask ‘what’s a 7155?’ I’d never heard of that model. He said don’t worry, you’ll know it, it’s just like the 5055 but it’s easier to operate.”

He headed to the gig at San Francisco’s Davies Symphony Hall. All he had for a contact was the name of the guy who left the voicemail, Ali.

“The security guy looks at me and gives me the head nod as I walk by with my little plastic fishing tackle box, all my Deadhead and Journey stickers on it. I walk in and come out on the stage. A bunch of guys in black suits are on stage, and one of them is doing a major rant. I look at the screen behind them. It’s gray scale, and it’s a mess. I look at the back of the house, see where the projector is and walk off stage. I wouldn’t know until later that I walked right past Steve.”

Jobs was the ranting guy, ranting because no one could get the GE to work, and without the GE there’d be no show.

“I get to the back of the house, in the projector room, look inside the projector and go, oh, okay.” It was simpler than the 5055, because it only projected black and white images.

“I dial it in.” The image on the screen pops into clarity. Jobs and the group suddenly see what is to them a perfect image on the screen. The rant stops.

“Cool. I fixed 90% of the problem. Now,” as is Steph’s way, he thinks, “Let’s take this thing out for a test drive.” He plays with the machine’s guts. The image morphs, flips, distorts. Then it’s perfect again. Then crazy again.

In retrospect, an observer would have seen a living cartoon, where the group on stage stares at the screen, motionless, then jumps around, swearing en masse, then motionless…

The group turned toward the back of the house, jumping up and down, frantically waving in that ‘you’re going off a cliff’ way. One of them broke away and sprinted toward the projection booth.

In the booth, Steph is unaware of the panic onstage. “I’m 150 feet away, I’m tweaking things, no one can see me and I can’t hear anything.”

A black suit bursts through the booth door. “Stop! Stop!! What are you doing? Who are you?”

A related aside: Steph has always been affable and approachable, and in these younger years we’re in here, his air of youthful, no hidden agenda innocence often deescalated stressful situations.

“I’m Steph, a guy named Ali called and said he had a problem with a projector.”

“You’re Steph? I’m Ali.”

They talk, Steph explains what he’s done to the projector. Ali is an executive with NeXT. The show, in a week, will introduce Steve Jobs’ new computer.

The event’s producer was well known in the Bay Area, and getting the projector ‘right’ will be a huge relief.

“Wow,” Steph said, “That’s great. So where’s your backup projector?”

“What do you mean? This is the only projector we have.”

Steph didn’t let the surprise make it to his face, and without lecturing he explained the unique challenges of the GE, how it required an operator to stay with it throughout its use, and if you had one you needed another, “because you’re never done with a GE,” especially for this event where the projector was critical to everything.

Ali thanked him, left the booth and rejoined the group onstage. Steph made some final adjustments, packed up, but as he walked out Ali stopped him and asked if Steph could come to the East Bay where they were rehearsing the show and set up a second projector they had just ordered.

Off to the side, Jobs targeted Steph with a direct, intense stare.

A few days later Steph arrives at a closed down, no longer used school. Ali and the formerly apoplectic black suits are there, including Jobs.

Ali led him to a large table. “We got the second projector,” pointing to several pieces of electronics and boxes.

Steph asked, “What’s this?”

“It’s the projector, it just needs to be assembled.”

It was the observation of a smart man who has no idea what “just need to be assembled” entailed.

GE didn’t have a 7155 ready and instead sent the parts to build one. “I called GE, we talked, and I put the projector together.”

An epic understatement.

He placed the projectors side by side, fired-up the first and stared at the screen image, “memorizing it,” his technical eye registering the image’s important elements invisible to mere mortals.

“Then I put up the ‘assembled’ projector’s image and dialed that in.”

Two GEs side-by-side created significant noise from their built-in fans (the beasts create heat when operating), but at one point the black suits had moved close enough for Steph to hear someone ask, “Who is this guy?”

It was Jobs asking Ali about him, and Ali responded, “That’s the guy who knows these projectors.”

Steph recalls that, “out of the corner of my eye, I could see Steve watching me, doing that stare.”

Twice now Steph had come in to a high stress situation and, without ego or agenda other than to make everything work, had tamed the beasts.

He and Jobs had yet to have a conversation.

A few days after the San Francisco event, Steph accepts the company’s request to do a site survey in San Diego for two small, future events that will be on the same day but in different locations, morning and afternoon. During a van ride with the NeXT team, one of the execs asks Steph, “So, what do you do?” and he explains his projection, audio, video, and staging services.

“Well, could you help us with these upcoming events?”

“That is what I do.”

A week later Steph and Bob Hartman, a projectionist he’d met working concerts and who would become one of A&A’s first four employees, drove a truck of gear to a San Diego hotel and set up the first show. Hartman then left to set up the second show in Los Angeles, and Steph immediately encountered an issue.

“There wasn’t enough power in the room to run the GE.” The machine, like light and sound systems brought in for big events, is directly plugged into the box where power comes into a building, as opposed to plugging into a wall socket, because it draws a lot of power.

“I ‘borrowed’ power from the hotel’s irrigation system, tapped into it. Their maintenance guy, kind of open-mouthed, asked what school I learned that from, and I said, man, this ain’t from school, this is rock and roll. I could tell he couldn’t quite grasp my explanation.”

The two events used identical presentations, each incorporating three state of the art (for their time) synchronized slide projectors, programmed to dissolve a projected image from one glass mounted slide to one on another projector, and back, and so on.

Steph got everything set for the first show, got in his rental and drove to join Hartman at the L.A. presentation. When he knew the San Diego show was over he called and asked his NeXT contact how it all went.

“Well, good, except for this one slide, there was this problem…”

Jobs was not happy about it.

Hartman could hear Steph’s side of the conversation, and as Steph asked which slide, Hartman jumped in, said, “It’s this one,” and cycled to it. The dissolve was slightly off on one slide. Out of sixty. A discerning eye might notice a shift in part of the slide’s design. Hartman had certainly noticed it.

That Jobs had noticed it was all that mattered now.

No matter what Steph and Hartman did, no matter how they adjusted for it, they could not fix it.

Steph said, “We’re fucked.”

When Jobs arrived he walked right past Steph, grabbed the slide projectors’ controller, rolled through to the problem slide, and went ballistic. “God damn it, can’t I get…”

Steph remembers, “I’d never seen a rant like that, not even the Davies Hall rant.

“Then I recalled my mom once giving me advice in my early years about another rant I witnessed: If you can learn to deal with this, you can deal with anyone.”

A bit later, “There was a small light backstage so you could see to walk around back there, and Steve was right under it, in that head down posture, talking with a woman from his team.”

Steph approached her after Jobs walked away. “Your guy is pissed. Here are the options: you don’t do the show, A&A goes home and there’s no charge; you do the show, we get paid, and we fix things when everyone gets home.” Minutes later the exec came back and said do the show then figure out how to move forward.

Except for the slide, it goes well. He and Bob strike and load out, and as Steph is leaving Jobs walks out of an office and sees him.

“Hi Steph.” It’s the first time Jobs has spoken directly to him. “How do you think it went?”

“Pretty good show.”

“What do you think about that problem with the slides?”

“Well, when we get home we’ll take a look and see what we can do about it.”

“See what we can do about it?” Jobs asked, leaning toward him. “What the fuck does that mean?”

In retrospect, it was a live or die moment, because there was only one response that would work. Steph didn’t ponder it nor did he shrink from the moment. “I said, poor choice of words. We’ll go home, fix the problem, and I’ll see you at the next gig.”

Jobs said, “Sounds cool. See you back home,” and casually walked away.

That exchange became the cornerstone of a relationship that would last more than a quarter of a century.

Outside, “I got in my truck and thought, huh, we’ve just cranked this up a notch or two.”

Their relationship matured, “because we quickly understood that we were looking at the same horizon,” shared visions in everything from clean design to the future of all things digital.

Steph has always been talkative, ready to share or absorb stories and perspectives. At Jobs’ home, the two talked at length about installing video projectors and lenses, “because he wanted to be able to work on videos and large graphic images at home,” discussed “how to make everything about the shows better,” and shot the breeze about kids and family.

On the road after rehearsals Jobs would grab him and say “let’s take a walk and get tea.” As their relationship tightened, Steph did what has always come natural to him, unaware that it was not a common occurrence, especially for someone outside of Apple: he told Jobs what worked well at the shows and what didn’t.

“It was a revelation for Steve, that he suddenly had knowledgable feedback about how the show looked from the audience perspective, and how it could be better. He didn’t have anyone to do that for him who also understood the technology, to show how and why specific fonts and particular colors were better for projected slide and video images.

“I began to take him aside and show him things, ‘hey look at this; if we do this instead of that,’ or ‘here’s what we can do to make this better.’ Like using particular stage lighting, not just throwing light up there to illuminate the stage, but instead how to style the lights to work with the show, work with the message.

“And how he looked on stage, how the audio sounded in the house. It was golden, because it mattered to him that it mattered to me. I was giving him, well, I was working in the same way as his teams, the difference was instead of a computer I was making him insanely great.

“He loved it. It marked another important turning point for us.”

One ‘hey, if we…’ Steph shared would become foundational in elevating Jobs’ keynotes to broadcast quality events. Over several conversations, Steph talked to Jobs about roadies and concerts, easy conversations because Jobs loved anything about music.

Rent the necessary equipment and the operators that came along with it was a then standard corporate approach to events. Generally, different audio-visual rental companies supplied everything from sound systems to video cameras, bringing systems and operators to a venue, operating the equipment during the show, breaking it down and taking it away.

In and out, do the show and leave. Pretty handy, easy as emailing or picking up the phone and asking for whatever you needed, but without consistency or quality assurance. A client wouldn’t know whether the equipment it had rented had been used at ten or one-thousand shows. Operators could make it all work and do the job, they certainly cared to varying degrees about getting everything right, but they had no skin in the game, no real investment in what was happening.

That’s no way to build a team, and Apple had ably demonstrated what exceptional teams could accomplish. What Steve Jobs needed was a road crew.

Concert tours had given Steph valuable insights into what enabled great live performances. A band’s audio, lighting, musical instrument, and stage technicians — the roadies — are essential to a band’s performance. Same equipment at each show, same techs who know the equipment, the performers, and the show. Same people moving it from place to place. Instead of technicians du jor, a band’s roadies were collectively vested in their work for, and with, ‘their’ band.

At a glance, roadies seemed a bit, well, raggedy around the edges, but while a band enthralled fans for a couple of hours, it was the roadies’ work before, during, and after shows that made the live performance possible. Steph recognized the technical acumen often camouflaged by roadies’ occasional MASH-like tendencies toward their work, and how well road crews meshed.

The concept was pretty damn far from what he’d experienced at times in the Bay Area’s corporate production arena, and as he talked it up with Jobs he could see him easily grasp the how and why it should be the same for producing consistently great keynotes.

That’s what happened. Steph put together teams consisting of the best people, who accepted that working with A&A and, by association, its client, was professionally and personally demanding in many ways.

Now legendary Apple confidentiality was one of the demands. A&A’s staff, crew, and vendors knew silence was the status quo. As Steph describes, “it was simple: if you’re not going to keep secrets, you’re not going to be here. I didn’t have to force people to maintain silence, I told them once and everyone understood. We had a curated team, people who live and breathe their skill set, with impeccable reputations.”

Crews, and then rehearsals, “became very efficient. Once we learned Steve’s idiosyncrasies, when we knew where he was going to walk, where he wasn’t going to walk, he’s going to use this microphone, then we could tune the room, tune the set up so he could walk in and work. When he knew the right team was there,” or as Jobs referred to them, ‘our guys,’ “it all became efficient for him.”

Steph produced every NeXT event from 1988 until a few months before the company’s end in 1997, all over the U.S., and in Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, Singapore, and more, approximately 400 events and shows. A&A’s client list grew to include many well known Silicon Valley companies, including Adobe, General Magic, Lotus, Oracle, Sybase, and SGI/Silicon Graphics, clients actively served by A&A as NeXT business slowed.

During the last few months of NeXT’s existence, an audio issue during a presentation and post-show scuttlebutt about it from someone not normally involved led to a mutual pause in their work together. Simultaneously, the company slowed to a halt, Apple acquired the company’s software, Apple CEO Amelio was fired, Jobs returned to Apple…and cleaned house.

Coming Up, Part Two -- The call to return, Steph’s most memorable show, and his toughest