The empty chair

You would have loved knowing Lou Naidorf

“Do you have a piece of paper?”

He would ask it at some point in every conversation. He knew I always had a notebook in my back pocket (for years it was a Moleskin which I still dig, but over the last year and for the discernible future it’s a Field Notes notebook), and a pen. Always.

For years, and years, we had an every couple of weeks meet and yack at Copperfield’s, a popular, local bookstore. It was convenient, a little less than halfway for me, a little more than halfway for him. I would have coffee, he hot chocolate, we’d split a chocolate croissant or poppyseed muffin, then sit in the bookstore’s small eating area and conversationally go…everywhere. We had commonality, aligned views on life and all its wonder, all its messes, sorrows, and its ever increasing number of WTFs. I’m old, but he had years on me. We truly liked each other, cared for each other, raged at injustice and stupidity, marveled at science and medicine, regaled each other with stories, shared secrets not to be shared with anyone else.

I was so blessed to have known him.

I was the last to visit his room and see him alive (his family’s location and some other issues prevented easy travel) but, in this instance, alive was relative. I counted a half-dozen IV setups, one bag on which I could easily make out the word Propofol. The ventilator kept him respirating, and the one time he was able to half-open his eyes in response to something I said, it was obvious that he was only barely still with us. And I had to be fully gowned, masked, and face shielded just to be allowed into his ICU room, which would have made it difficult to converse with anyone no matter their condition.

He’d had several health issues, a couple significant, in recent years. The slow decline had frustrated him, wore him down bit by bit. His caretakers most certainly helped him stay around for longer than if they hadn’t been there.

The morning after I’d said my goodbye I came into our kitchen at home for coffee and my wife said that his daughter had called. “Lou died last night.” It was the day before what would have been his 97th birthday.

Lou Naidorf was extraordinary. Not a Superman bullets bouncing off and leaping tall buildings in a single bound way. He was a smaller man with a giant intellect, with no room in his life for fools or egomaniacs, nothing but love for his wives — and women in general — and a special affection for any architectural student, especially those he encountered walking the campus of the small Southern California college where he served for a time as board member and occasional teacher. His counsel, interest, and sincerity changed more than a few lives.

His name is not as well known as the fingers-on-one-hand architects’ names familiar to some of the general public, but his buildings… Oh, those buildings.

He grew up poor but never realized it until a few years ago; couldn’t recall having toys of any kind but wasn’t bothered by that; didn’t have a room so slept in a closet. Liked and did well in school.

He didn’t ‘miss’ having toys, because he would spend hours playing with cereal and food boxes, sitting on the kitchen floor stacking and organizing them.

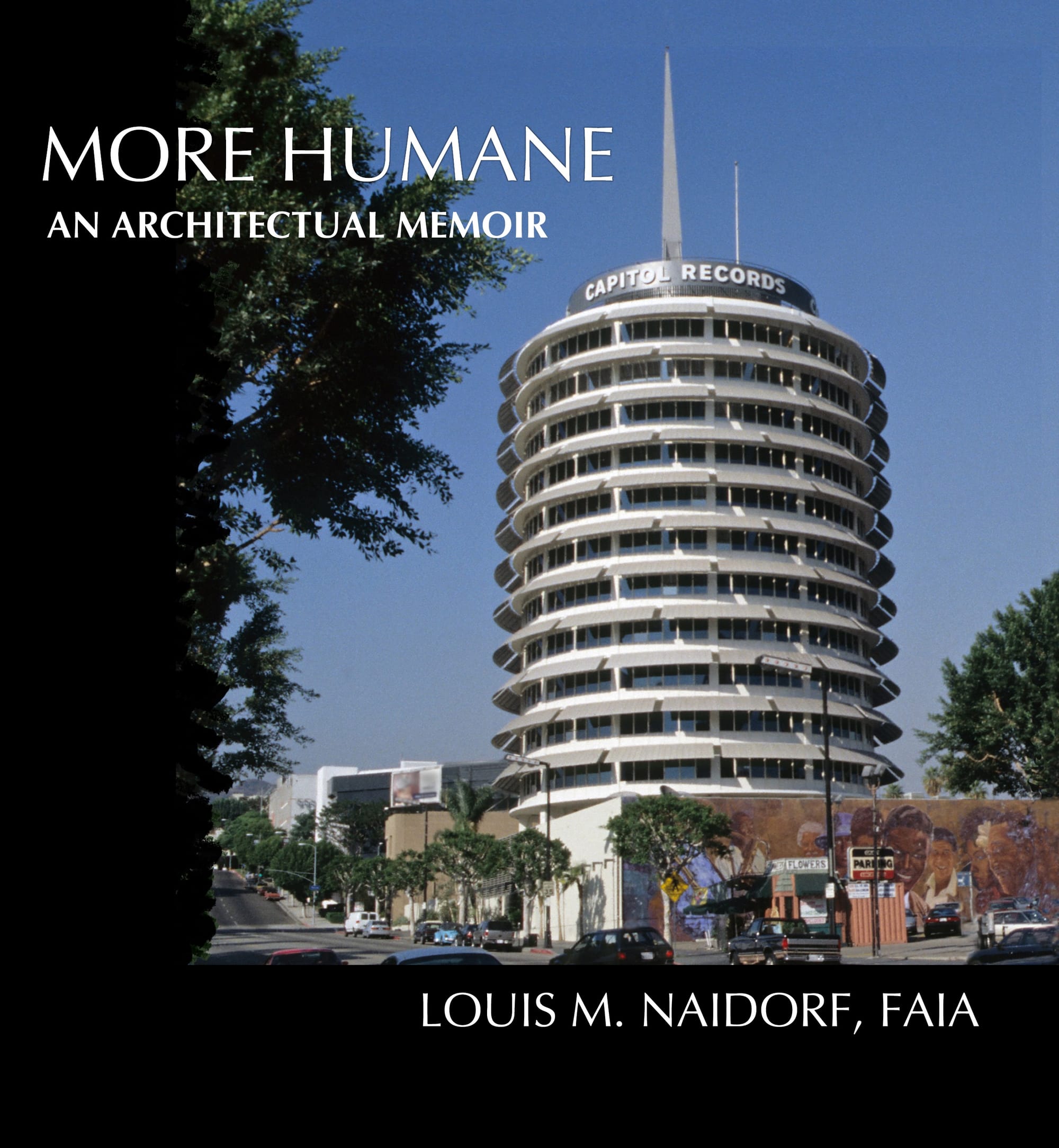

He made his way to UC Berkeley, graduated from the architectural school a year early and, barely old enough to vote or have a drink, landed his first commercial architect job with Welton Becket, the head of a historic Los Angeles architectural firm. Shortly after came his first project as lead design architect for an unnamed client, to design a new office building on a small plot in L.A.

It would not simply change his professional life, it would alter the very look and feel of Los Angeles. When completed, it would also become its own apocryphal origin story: the Capitol Records tower, the building based on the idea of a stack of records, a myth that continues to this day, although enough has finally made it into the historical record that moire than a few now know that was not its origin at all. It was in reality based on the available space of the lot; a few odd requirements for how the building would be used; and the mind of a great architect in the making.

Any architect could have put something up that fit the specs but, truly, only Lou could have envisioned the building’s to-this-day unique design.

That’s because Lou had already envisioned it while still in school. When confronted by the lot’s confined space and the building’s operational requirements, the concept he had first created for his university Master’s thesis was the perfect solution to Project X, the only client name he was permitted to know.

The building certainly defined him in many ways for the rest of his life, something he vacillated upon from frustration to acceptance, and back again. Several of his other buildings also altered not just the perceptions of architectural style but, as was his trait, added a highlight to a city skyline. Truth be told, I have a fondness for the Dallas Hyatt over the Capitol Records tower, in part because of its design, in part because of my own memories of having stayed there several times.

For years, and years, I cajoled, encouraged, pushed Lou— occasionally to a point just this side of obnoxiousness — to write his story, offering to assist in any way I could. I did this for the same reason I pushed my close friend Steph Adams to share the story of his three decades side by side with Steve Jobs: the journeys to their places in history were not just unique, they’re both wonderful people such that their stories were wonderfully humane.

When Lou finally did put pencil to paper (he had a Mac, but used it only grudgingly, and never to compose or design), and we put a memoir together to be given only to family, friends, and a select group of compatriots and peers, he titled it More Humane. It was his core philosophy and guiding principle of every space he ever turned into a structure or defined landscape. For all the professional accolades, what pleased Lou the most was what had been said to him unsolicited by people who spent time in his buildings, that they liked being inside them, they liked seeing his building as they approached it.

He might have been a remarkable architect with an AIA Lifetime Achievement recognition, but his greatest source of pride was knowing his work made people feel a little better about their lives.

So there we’d be, laughing, kvetching, our conversation often paused so he could share a thought or observation with someone passing our table. I have those quickly drawn, visualized thoughts and ideas, which might be interpreted as simple geometric shapes and direction by someone who didn’t understand the magic in the lines’ creation, or in their creator.

The Los Angels Times had a featured story the next morning about Lou and his passing, and in the next day’s print edition. The wonderful journalist who penned it, Pamela Chelin, had first established her friendship with Lou when she had contacted him to write a long piece about the Capitol Records building and its architect. She and Lou subsequently developed a long distance phone friendship after that first piece.

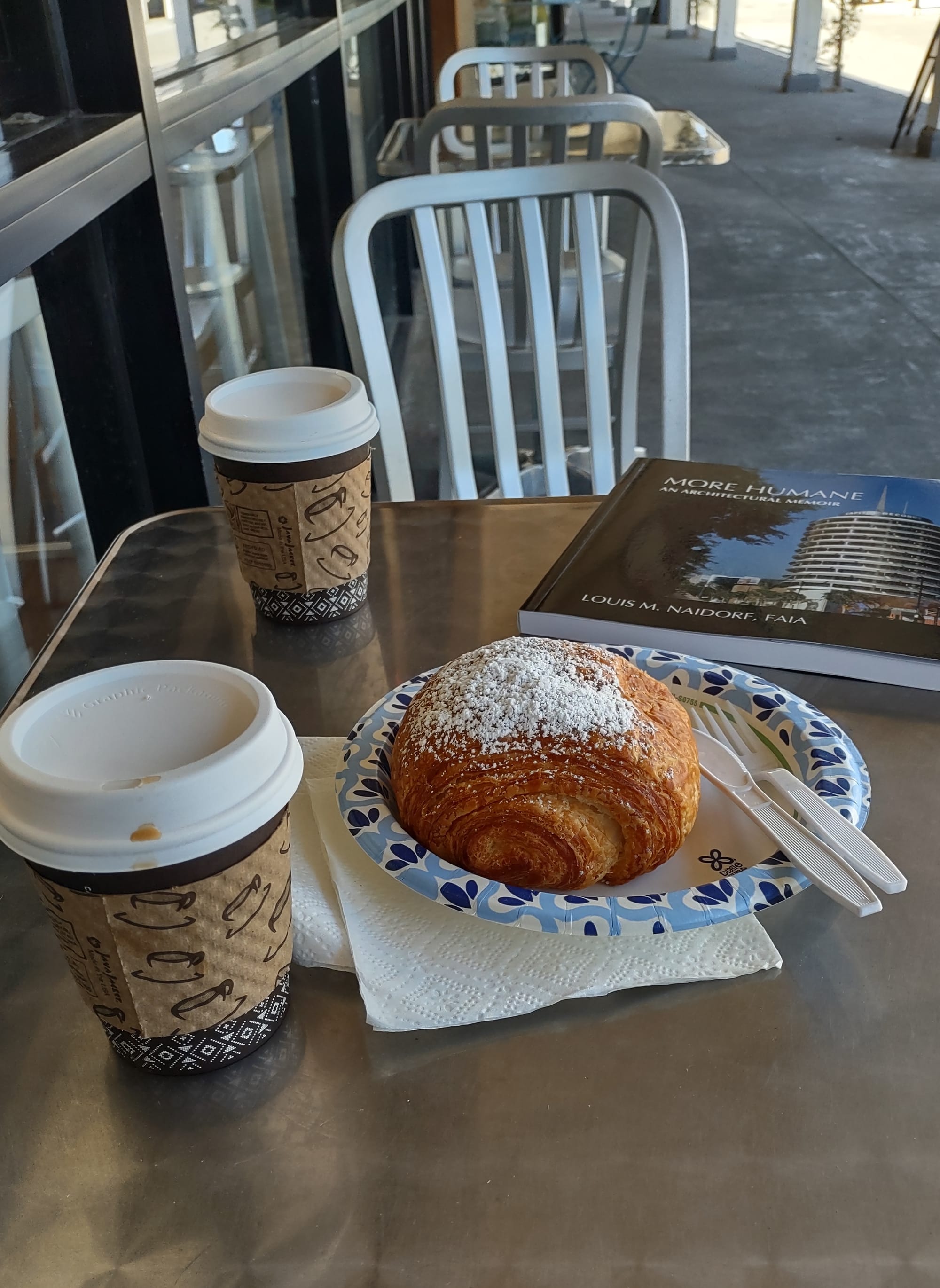

In the afternoon on the day after he died, I went to the bookstore cafe’, ordered a coffee, hot chocolate, chocolate croissant, and brought it all to an outside table. I placed his book across from me, snapped a picture, then simply sat and let those past days and conversations float through my head.

After a few minutes a gent from another table came over and asked, “Do you mind if I take this chair?” Two women he was with were at the table next to mine and he was going to join them. I hesitated a moment before saying yes, and he noted it, glancing at the book and cup, and asked, “Are you sure?”

I had to smile, and said it’s fine. It was a fitting karmic end to a special, singular relationship. I’d never need that chair again.

Lou would have loved it.